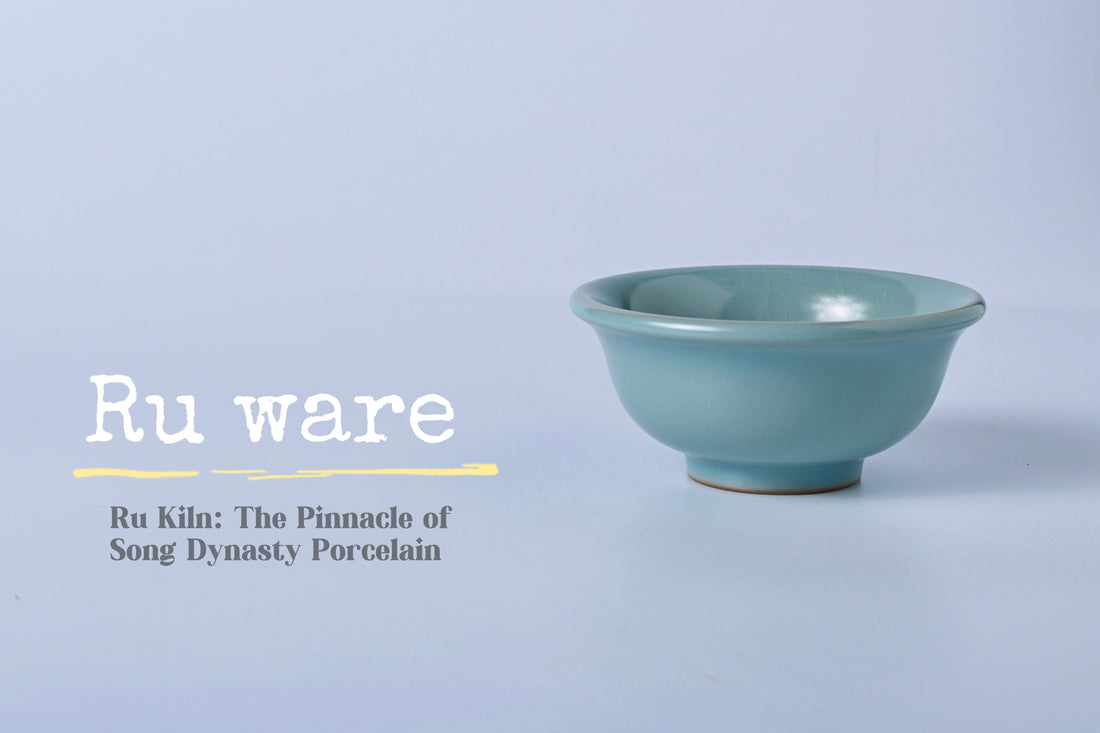

Ru Kiln: How Emperor Huizong’s Aesthetic Defined the Peak of Song Porcelain

Song Porcelain – The Pinnacle of Chinese Aesthetics

As Ma Weidu once said: “Song porcelain is the pinnacle of Chinese aesthetics.”

During the Song Dynasty, porcelain developed in a way unseen in any other era. It was divided into two major systems: official kilns (guan yao), which reflected the refined tastes of the emperor, and folk kilns (min yao), which emphasized practicality. Famous folk kilns include Cizhou and Longquan, while the imperial kilns—commissioned by the court—reached unprecedented artistic heights, particularly under Emperor Huizong of the Northern Song (r. 1100–1126).

Among the Five Great Kilns of the Song Dynasty—Ru, Guan, Ge, Jun, and Ding—the Ru Kiln has always been regarded as the most prestigious. Its most celebrated feature was the sky-blue glaze (tianqing you), which Emperor Huizong found irresistible. Ru ware became imperial porcelain, produced with no regard for cost or time. Craftsmen even added powdered agate into the glaze, giving the surface a jade-like, silky texture.

The Legend of “Sky After Rain”

Legend tells us that Emperor Huizong once dreamed of a sky clearing after rain and was captivated by its unique color. He commanded artisans to reproduce it in porcelain, famously declaring: “When the rain clears and the clouds break, capture this color.” Many craftsmen struggled to achieve it, but the artisans of Ru prefecture succeeded—thus the legendary Ru Kiln glaze was born.

Distinctive Features of Ru Kiln Porcelain

Color: Soft, natural, and elegant, with hues such as sky blue, moon white, bean green, and lake blue.

Texture: Glossy, moist, and jade-like, with a gentle resonance when tapped.

Crackle Patterns: Because glaze and body shrank at different rates during firing, fine crackles appeared. These included cicada-wing lines, crab-claw crackles, willow-leaf crackles, and ice crackles. What began as technical flaws became highly prized decorative effects.

Bubbles: Under magnification, tiny air bubbles in the glaze appear scattered like “sparse stars at dawn.”

Sesame-Seed Spur Marks: To achieve a fully glazed surface, potters used tiny spurs to support the vessels during firing. After firing, these left behind tiny marks resembling sesame seeds—an identifying hallmark of Ru ware.

Shapes and Forms

Ru ware was crafted not only as everyday utensils like bowls, dishes, and plates, but also as court display pieces inspired by bronze vessels. Famous forms include tripod censers with string patterns and lotus-petal warming bowls. Common features include outward-curving rims, echoing the design of contemporary gold and silver wares.

Famous Examples

Sky-blue tripod censer with string patterns – Inspired by Han bronze vessels, cylindrical in form with three legs, smooth jade-like glaze. (Palace Museum, Beijing)

Lotus-petal warming bowl – Shaped like a blooming lotus, with elegant curves and delicate crackle glaze. (National Palace Museum, Taipei)

Sky-blue Ru basin (wash) – Simple, wide mouth, shallow belly, supported by three feet, with clear sky-blue glaze and natural crackles. (Palace Museum Beijing, British Museum London)

Origin and Kiln Sites

The name Ru Kiln comes from its location in ancient Ruzhou, covering modern-day Ruzhou, Baofeng, Lushan, Xiangcheng, and Jia counties in Henan. The main kiln sites were discovered at Qingliangsi and Hanzhuang villages in Baofeng County, near Pingdingshan, Henan.

Development period (mid-Northern Song): From Emperor Renzong’s reign (1023) to Shenzong’s reign (1085), production expanded, decorations became more elaborate, and glaze effects more refined.

Peak (late Northern Song): Ru ware was chosen as tribute porcelain, and later became an official court kiln under Emperor Huizong’s reign. Scholars debate the exact date it became an imperial kiln—likely between the Zhenghe (1111–1118) and Xuanhe (1119–1125) eras.

Decline (late Northern Song): Production halted during the Jurchen invasion and political turmoil. The techniques were lost. During the Jin and Yuan dynasties, folk kilns continued to imitate Ru ware, but with thicker bodies, rougher workmanship, and incomplete glazes.

Rediscovery of the Kiln Sites

For centuries, the exact location of Ru kilns was a mystery. In 1977, ceramic experts Feng Xianming and Ye Zhemin from the Palace Museum identified shards with typical sky-blue glazes near Qingliangsi, Baofeng. Later excavations in the 1980s confirmed the site. In 2000, another kiln site was found at Zhanggongxiang in Ruzhou, showing similarities to Ru ware but also distinct characteristics.

The Legacy of Ru Kiln

Ru Kiln porcelain embodies the ultimate expression of Song aesthetics—restraint, elegance, and natural harmony. It represents not only imperial taste but also the extraordinary technical skill of Song artisans. Though its production lasted only about 20 years, surviving pieces—fewer than 100 worldwide—are today regarded as national treasures, housed in the most prestigious museums.

Ru ware is not merely porcelain—it is the material realization of Emperor Huizong’s dream of the perfect sky.